In parenting, there has been a paradigm shift away from managing behavior to being responsive to our child’s nervous system. Children’s ‘difficult’ behaviors may often seem random and unpredictable, but they aren't necessarily so when you understand what’s behind them. Increasing knowledge of brain development helps us make sense of child behavior, and when we know better as parents, we do better.

The child's developing brain

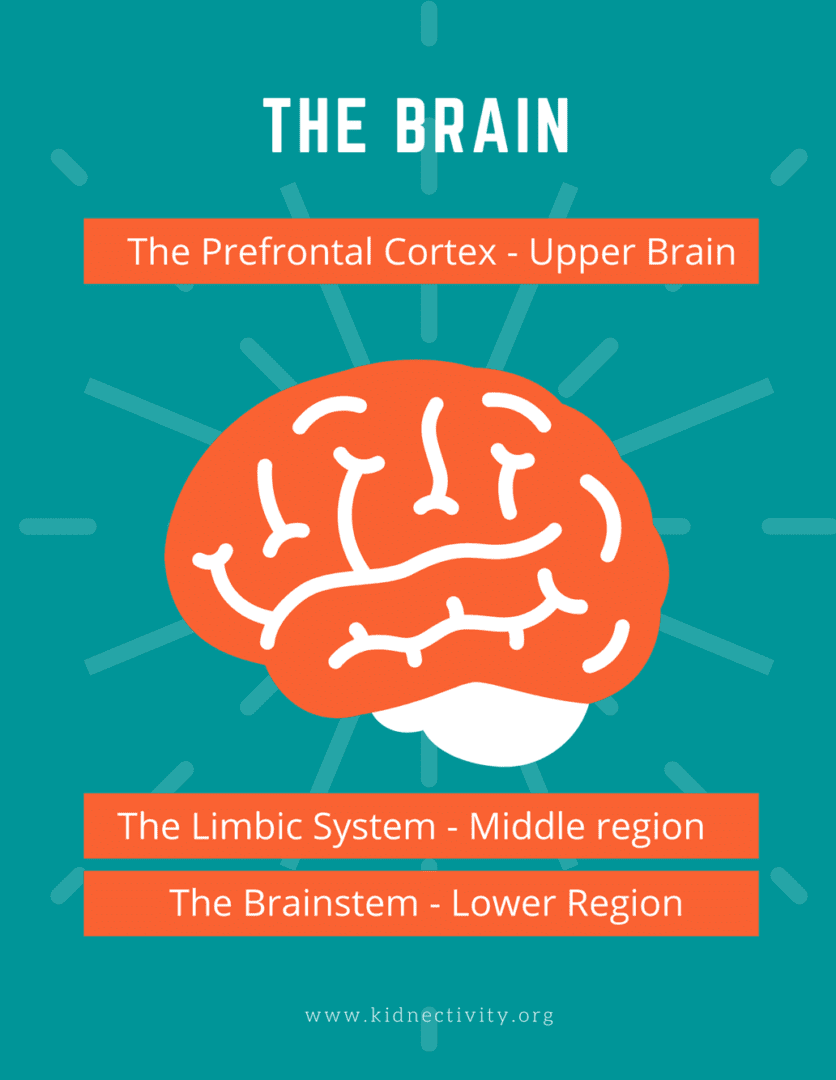

Lower Region

The lower region, the brainstem, is fully developed at birth. It is responsible for regulating breathing, digestion, sleeping, and many other unconscious bodily functions. Every parent is well aware of how being tired, hungry, thirsty or sick can be a catalyst for epic meltdowns. Dr. Daniel Siegel, pediatric psychiatrist and co-director of UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center, uses the terms upstairs and downstairs brain. The brainstem is one of two areas within the downstairs part of the brain.

Middle Region

The middle region is the limbic system, which houses the amygdala, and is the second part of the downstairs brain. The limbic system is the emotions center of the brain. This area develops rapidly in early years and governs your young child’s behavior. Our limbic system is responsible for protecting us from harm, whether real or perceived. This system produces our survival response, fight, flight, or freeze.

When the amygdala senses a threat it takes control, limiting access to the upper region of the brain. A threat can include feeling overwhelmed (sensory overload or emotional), not getting enough attention (seeking connection), anxious, scared, fatigue, or not feeling well. Sometimes a child’s brain and body register threats that might be invisible to a parent, which is sometimes why it appears that our child’s challenging behaviors “just come out of nowhere.”

Upper Region

The upper brain, which includes the prefrontal cortex, houses the “thinking brain.” This is where logic, language, reasoning, self-control and emotional regulation occur and takes decades to fully mature (around age 25). This is what Dr. Siegel calls the upstairs brain. Brains develop from the bottom up. When we remember that our kids do not have a fully developed brain it can help us have a little more compassion and patience with them.

The Children's Brain Duirng Meltdowns

When a child perceives a threat, reasoning and language are inaccessible. The part of the brain most active during this time is wired for survival and protection. When the brain is in survival mode, it switches us into fight, flight, or freeze. This mode is how all brains protect themselves from danger, potential harm, or threats (real or perceived). This is when we see such behaviors as hitting, kicking, running, screaming, crying, yelling and other challenging behaviors described during meltdowns. It is your body gearing up for battle because the brain feels or perceives we are in danger

During big emotions it isn’t that our children are being bad, but rather that they are feeling bad and haven’t mastered the ability to control their impulses, dampen their reactive amygdala, communicate their wants and needs, or think ahead to the consequences of their actions.

How Can I help calm my Child?

Knowing our brains are not fully developed until we’re in our mid-20s can help us understand why our children behave the way they do. In the end, this allows us to parent better during challenging situations. This knowledge can help shift our thinking to guiding rather than punishing children.

If we scream or threaten punishment while a child is in the midst of a meltdown, their brains continue to perceive this as a threat and their amygdala goes into high gear and begins to take charge. Even telling a child to “calm down” in these moments only adds to their stress. This is why, when a child becomes emotionally dysregulated, it becomes difficult to reason with them and oftentimes only adds fuel to the fire.

Dr. Bruce Perry, a child psychiatrist and neuroscientist, uses the concept of the “Three Rs”: Regulate, Relate, Reason. We first need to regulate, in order to relate, and only then can we reason with the child.

1. Regulate the Downstairs Brain

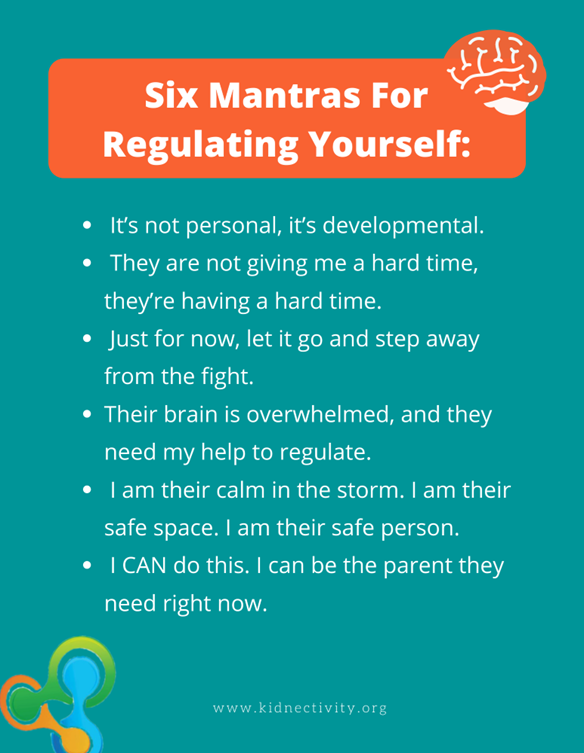

During times of high emotions, parents should first regulate their own emotions. It’s crucial, although more easily said than done, to remain calm and avoid fanning the flames. Dysregulation is contagious, so don’t join the chaos!

Adults who are regulated can then move on to help children calm their stress response (co-regulation).

Regulating children is most successful when they are guided by a trusted adult. The strength of this trust is built over time and based on past experiences.

Begin soothing a child by making them feel calm, safe, and loved. We can communicate comfort not only with our words but with a soothing tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, and being at or below their eye level. If a child is overwhelmed, you can guide them to a quiet spot and give them the space they need to begin to calm.

2. Relate Via the Limbic System

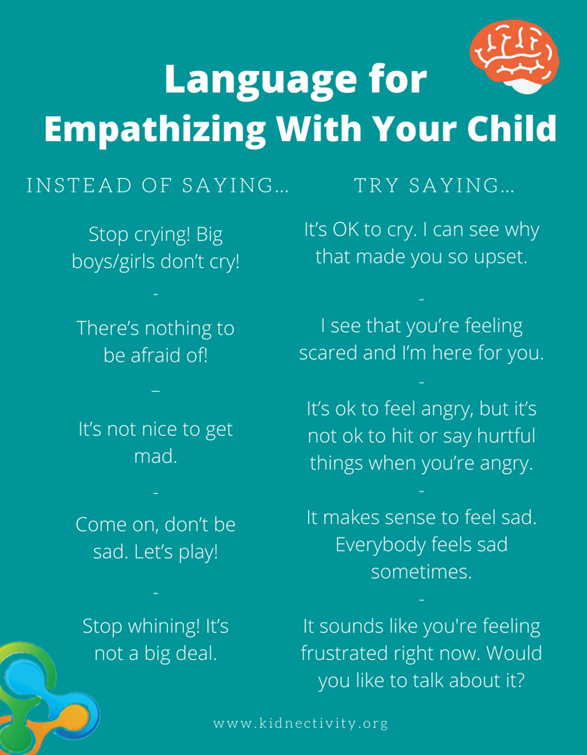

Once you sense the child is calming down, the parent can move to the relating part. The focus here is on connecting with your child and helping them by empathizing and validating their feelings so that they feel heard, seen, and understood. It signals that you understand what they are feeling without trying to talk them out of, dismiss, or shame them for it.

Acknowledging the feelings also doesn’t mean that you accept the behaviors of the child or are rewarding negative behavior. Children still need boundaries and limits for safety. It’s okay to accept and acknowledge their big feelings as well as calmly and confidently hold boundaries. As Dr. Siegel states, “Say yes to the feelings, even as you say no to the behavior.” Our goal is to teach our children that they can experience difficult feelings without acting on them.

3. Reason via the Upper Brain

Once the child is feeling connected, back to a regulated state and no longer overwhelmed with emotions, we have the opportunity to reflect on what happened.

During this time, talk about and learn alternative behaviors and strategies for the next time emotions overwhelm them. This helps build a child's ‘toolbox’ of strategies to express and process their emotions in a healthy, safe way. It is important to remember that coming down from those strong emotions takes time, sometimes even hours.

As an example: “Earlier today when you wanted to stay at the park and said “I hate you,” I noticed you were really mad. I’ve felt that way before too. Let’s talk about what happened and brainstorm ideas to make leaving the park easier.”

Three Strategies for reasoning:

1. Model

Modeling how we work through our own emotions is the best way to teach children how to work through theirs. As parents, when we experience emotions, we can discuss them openly with our children. Sharing difficult moments, and how we manage them, is a powerful tool.

When we become worried, frustrated, sad, etc, we can: name the emotion, narrate what we’re going to do to try to handle it, such as taking deep breaths or remove yourself from the situation, and discuss what happened once we are calm. For example, ‘I’m worried this traffic is making us late. If I take some deep breaths, it will help me stay calm.”

Additionally, if you find yourself reacting to your child by screaming, slamming doors, or a myriad of other behaviors we’re not trying to teach, use this as an opportunity to apologize to your child and how you could have handled the situation better.

2. Teach the language of emotions

The goal of teaching about emotions is having our children understand and manage their emotions. When we teach kids that their emotions are valid, we help them view what they feel is normal and manageable. It’s important for children to understand that emotions and feelings are temporary and that their unpleasant emotions won’t last forever.

It’s helpful to explain to children that everyone has feelings. Some emotions might feel good while others make us feel uncomfortable. All emotions are okay to have, even the ones that make us unsettled or uneasy.

Take time to actively notice and name emotions with your children. This can be done by labeling your own feelings as well as observing what your child and others are feeling, all in a non-judgemental, accepting way. Everyday situations, including while reading books, provide opportunities to talk to kids about emotions:

- “He sure looks angry.”

- “Why do you think he looks so sad?”

- “How do you think he feels now?”

3. Review and reflect

A regulated, connected adult and child can now begin to review and reflect on what happened. Use this opportunity to help your child understand that they were overwhelmed by their emotions and not to “teach a lesson” or lecture about what the child did wrong. Briefly talk about what occurred and, if able, help your child form a story about the meltdown, including what initially upset them.

Work together to brainstorm strategies and tools for managing overwhelming emotions and behaviors that occur in the future. Problem-solving together is empowering for a child. Ask questions such as, “What could you do instead…?” or “How can I help you next time?.” The goal is to help your child learn from the experience and give them tools to express their emotions safely.

I can be the parent my child Needs

Understanding a bit about our child’s brain and its development gives us insight into some of their behaviors. When children display challenging behaviors it can be difficult to recognize it as a need for connection, validation, and guidance. Underneath the defiance, tears, and yelling is a child who needs to feel safe. Tantrums and meltdowns are not a reflection of our parenting skills, but rather a reflection of our child’s developing brain. Our expectations of our children need to be in step with that.

Our brains and bodies learn through patterned, repetitive experiences; therefore guiding our children is a process that takes time, patience, and many do-overs. Each time we show up providing safety and connection during stressful moments, we help our children develop skills they need to effectively manage emotions, stress, and the ever changing demands of life.

As parents we are constantly learning, but the most important lesson is that there is no such thing as perfect parenting. As Dr. Carla Naumberg, clinical social worker and author, states. “You don’t need to be a perfect parent to be a great parent.”